Guest Contributors: Torian Easterling and Jahmila Edwards

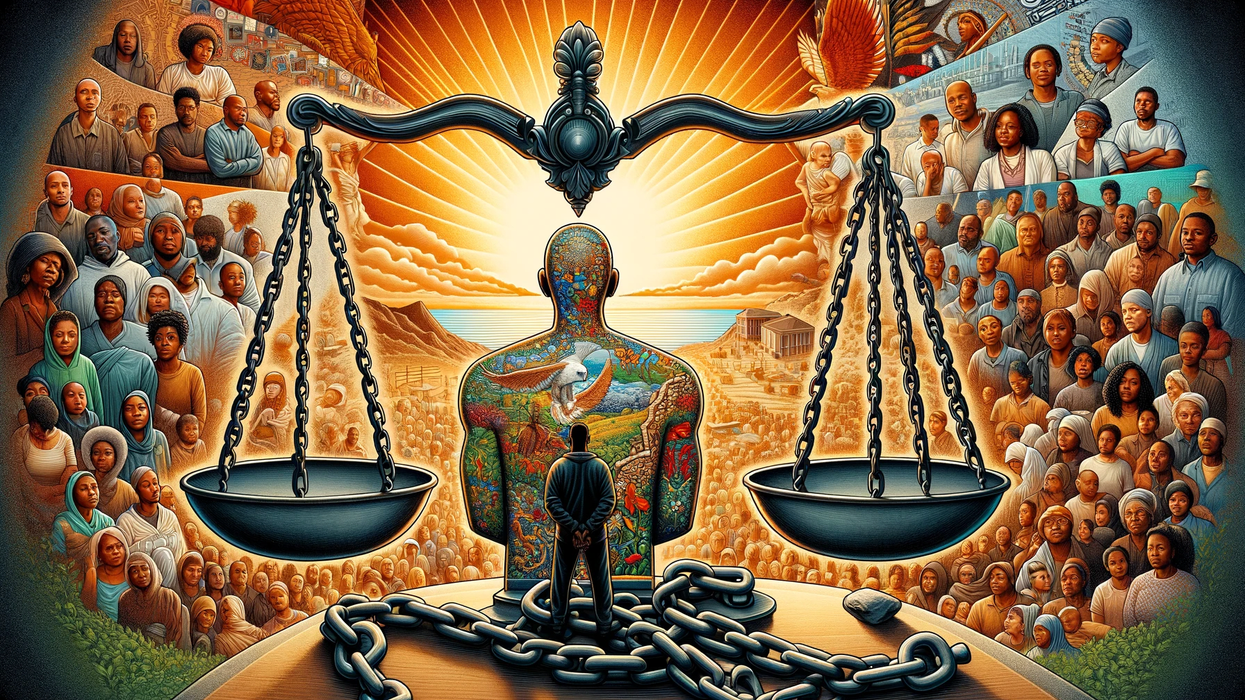

Racial inequities in New York State have long existed, fueled in part by structural racism, and longstanding and chronic divestments stemming from federal and state laws. These inequities shape many facets of communities and individuals, including access to high quality, preventative healthcare. In New York specifically, the inaccessibility of healthcare translates into a lack of medical cannabis for otherwise deserving patients.

New York is correctly prioritizing the expansion of medical cannabis alongside growing the adult-use market. This will help individuals who are currently in the medical cannabis program and can expand education and access to individuals and communities who have been disproportionately impacted by racist policies, if properly invested. However, as with everything in cannabis, the equitable solution is more complicated than just approving licenses to qualified medical cannabis operators. Before providing a suggested solution, let’s unpack the impact of racially biased anti-drug policies on communities of color and low-income communities across New York State.

Incarceration and Financial Stability

Interactions with the criminal justice system are shown to increase unemployment, a reliance on alternative and often lower quality jobs, and a sustained loss of earnings. Because of drug-war policies nationally and in New York (most notably the Rockefeller Drug Laws), a significant portion of those incarcerated have been drug offenders, particularly members of Black and Latinx communities. Misdemeanor arrests played a significant role in drug-war and related quality of life policing strategies popularized throughout New York and were often connected to higher rates of pretrial detentions which drive unemployment and lost income.

Additionally, it is important to note one particular impact: the startlingly high rate of imprisoning women and mothers. In New York, the female jail and prison population increased by 190% and 272% respectively between 1980 and 2017, driven in no small part by drug convictions. By 1999, women of color comprised 91% of women convicted of drug crimes in New York, despite being 32% of the state population.

Female incarceration not only impacts individual women, but often the economic well-being of entire families. In 2017, more than 8 out of 10 women in New York City jails alone were mothers, with drug crimes being the primary reason for detention historically. Most crucially, maternal incarceration increases the chances that their children will be incarcerated in the future, producing intergenerational economic devastation.

Fortunately, under the MRTA and other legislation, nearly half a million people have seen their cannabis- related convictions expunged, providing relief from future disclosures of economically harmful information.

Housing

Stable, safe, and quality housing is well recognized as an essential determinant of health. However, housing policies under the War on Drugs have driven housing insecurity, homelessness, and poor health outcomes by zealously relying on evictions and policing housing to address the “prevalence” of drugs in residential settings.

Between 1988 and 1998, anti-drug fervor mobilized the passage of sweeping bills focused on eliminating drugs in housing. Through these bills, the federal government made public housing tenants increasingly vulnerable to drug related evictions. First, it penalized drug users, then those they lived or affiliated with. As a direct result of these policies, nearly 5,000 people were permanently excluded from NYCHA alone between 2007 and 2014. More strikingly, over 111,000 New York City residents have been at risk of being denied housing since 1980 for only drug offenses, nearly 50,000 of which were made vulnerable for merely possessing drugs.

Because so many individuals have interacted with the criminal justice system, are affiliated with justice-impacted people, or have barriers preventing them from meeting drug-related housing requirements, hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers have faced unstable living conditions as a direct result of drug-war policies.

Education

Similar to housing, drug-war education policies focused on resource deprivation and punitive enforcement. After several decades, youth in low-income and minority communities have and continue to suffer long-term consequences. Access to higher education for people with records of drug offenses, no matter how minor, has been limited through both mass incarcerations, as well as specific legal exclusion. After the 1984 Anti-Drug Abuse Act passed, research shows a demonstrable decrease in college enrollment among Black men because of heightened drug-related incarceration rates.

However, it was not enough to penalize just the incarcerated, or those pursuing higher education. Under Reagan, primary and secondary schools were recognized as a key site for “confrontational”, anti-drug strategies. Suspension, expulsion, and other zero- tolerance policies were popularized through anti-drug rhetoric, and the number of school police officers skyrocketed as drug-war strategies evolved. By 2008, the NYPD’s School Safety Division alone was the fifth largest police force nationally.

Putting police officers in schools may placate safety concerns, and anecdotal evidence suggest their usefulness in certain instances, but evidence shows policing children has, in the aggregate, widened educational opportunity and achievement gaps. Police intervention involving students is shown to reduce individual educational outcomes and produce high rates of emotional distress and PTSD which further impairs academic achievement. Furthermore, schools with more punitive practices following zero- tolerance, drug-war logic see lower achievement among all students, and higher subsequent rates of adult crime. Students in areas with high rates of police violence and brutality already see diminished GPA’s, making interactions with the police in schools all the more devastating. In New York State, these racial disparities and associated harms to learning begin as early as elementary and middle school.

Compounding Impacts

Holding the above social determinants of health in isolation offers a window into how drug-war policing and policies have impacted each specifically. However, lives cannot be compartmentalized so easily, and it is important to acknowledge that each social determinant of health has demonstrable impacts on one another. Beyond worse health outcomes, low quality or unstable housing is connected to lower educational attainment and academic achievements, as well as diminished financial stability. Unsurprisingly, higher education leads to higher income, higher quality housing and even higher housing values. The inextricable connection between these determinants also causes mutually reinforcing consequences. For example, economic hardship not only narrows housing opportunities, but increases housing inequalities in the aggregate thereby “locking less advantaged people in less advantaged places.” In considering the impact of drug-war policies on impacted communities, it is important to remember that while these strategies focused on discrete aspects of individual interactions and lives, the effects ripple through every aspect of a person’s life.

By unpacking the interconnected and cascading consequences of the War on Drugs, we can see clearly how communities hit hardest by drug criminalization have reaped the fewest benefits of medicalization.

About the Authors:

Dr. Torian Easterling is senior vice president for population and community health and chief strategic and innovation officer at One Brooklyn Health and founding partner of Black Star Wellness. Dr. Easterling previously served as the first deputy commissioner and chief equity officer at the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Jahmila “JJ” Edwards is a dynamic leader with more than 15 years of experience working at the intersection of government, policy and politics in New York City. She is associate director of District Council 37, New York City’s largest public employee union.

11 Signs You've Greened Out and How to Handle It - The Bluntness

Photo by

11 Signs You've Greened Out and How to Handle It - The Bluntness

Photo by  11 Signs You've Greened Out and How to Handle It - The Bluntness

Photo by

11 Signs You've Greened Out and How to Handle It - The Bluntness

Photo by

How to Make a Cannagar Without a Mold: A Comprehensive Guide - The Bluntness

Photo by

How to Make a Cannagar Without a Mold: A Comprehensive Guide - The Bluntness

Photo by

The Puffco Peak Pro brings style and ease to cannabis dabbing.Image from Puffco on Facebook

The Puffco Peak Pro brings style and ease to cannabis dabbing.Image from Puffco on Facebook The Puffco Peak Pro is easy to hold AND easy to use.Image from Puffco on Facebook

The Puffco Peak Pro is easy to hold AND easy to use.Image from Puffco on Facebook The Puffco Peak Pro allows you to appreciate cannabis and innovation at the same time.Image from Puffco on Facebook

The Puffco Peak Pro allows you to appreciate cannabis and innovation at the same time.Image from Puffco on Facebook

What will you do with that cannabis kief collection? - Make Coffee! The Bluntness

What will you do with that cannabis kief collection? - Make Coffee! The Bluntness DIY: How to Make Kief Coffee - The Bluntness

Photo by

DIY: How to Make Kief Coffee - The Bluntness

Photo by

What is reggie weed? - The Bluntness

Photo by

What is reggie weed? - The Bluntness

Photo by